About the artist

Rob Buelens / 25.07.1989 / Londerzeel, Belgium based artist

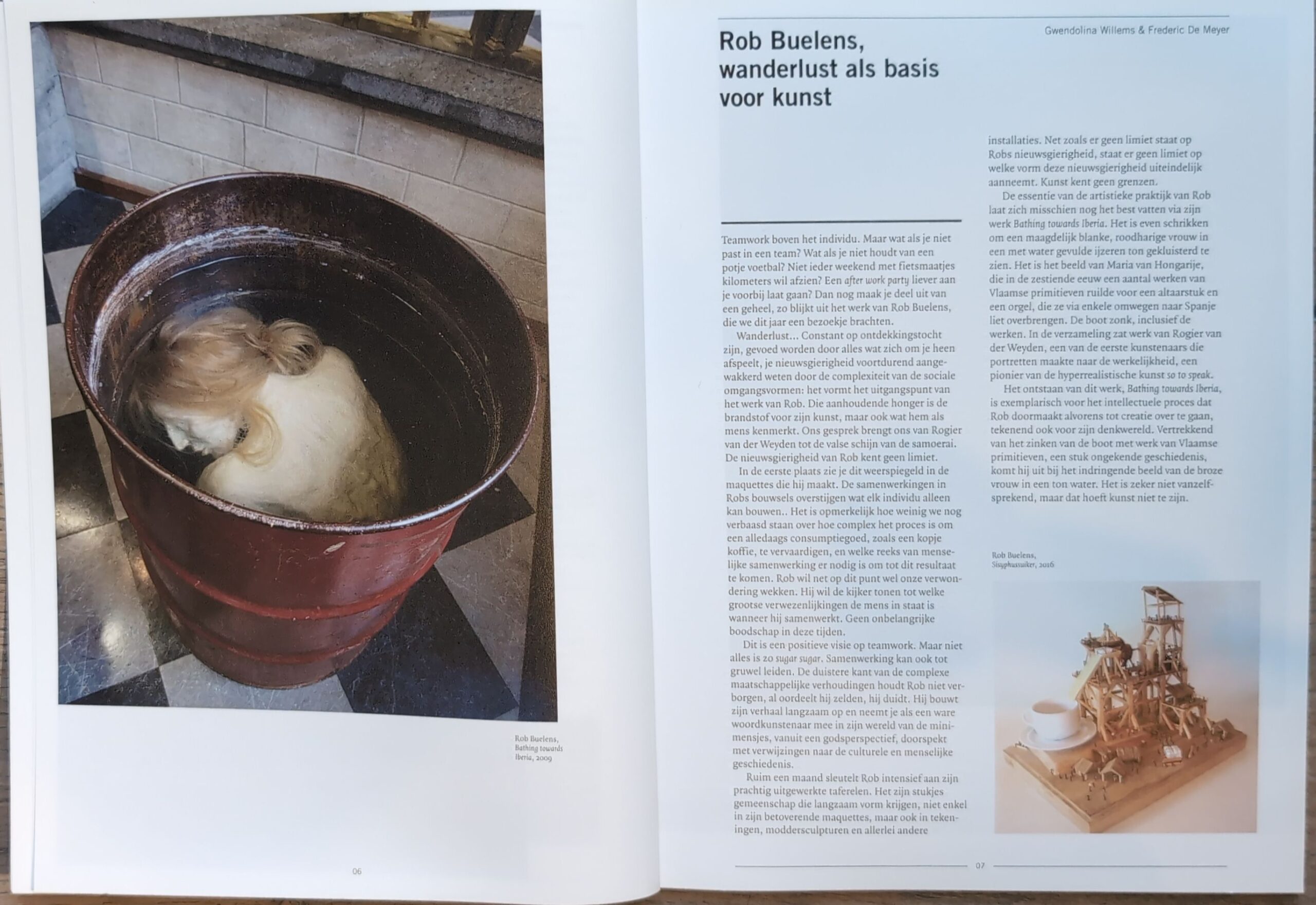

Education

Secondary school, Sint Lukas Brussels

Bachelor Liberal Arts, Sint Lucas Antwerp

Master Liberal arts, Sint Lucas Ghent

SLO (teacher’s education), Sint Lucas Ghent

Curriculum Vitae / Exhibitions

/ PAN Amsterdam

24/11/2024 – 01/12/2024

/ Coutre MAM

Gent

19/09/2024 – 27/10/2024

/ All under Heaven

Puurs-Sint-Amands Cultural center ‘Binder’

06/09/2024 – 24/11/2024

/ Kunst Rai

27/03/2024 – 01/04/2024

/ Vertigo Gallery (Antwerp)

24/11/2023 – 22/11/2023

/ PAN Amsterdam

19/11/2023 – 26/11/23

/ Walking on thin Ice Curator: Lieven Cateau

Zottegem

18/06/2023 – 16/07/2023

/ PAN Amsterdam

20/11/2022 – 27/11/22

/ Kidmie

Schellebelle

04/09/2022 – 25/09/2022

/ Atelier in beeld

Arts Monopole Puurs-Sint-Amands

13/05/22 – 15/05/22

/ Out of the box

Klub Solitaer Chemnitz Germany

16/07/22 – 27/08/22

/ Kunstrai Art Amsterdam

03/05/22 – 07/05/22

/ PAN Amsterdam

22/11/21 – 29/11/21

/ ORBEM NOVIS Curator: Daan Rau

Morbee Gallery, Knokke-Heist

04/09/21 – 07/11/21

/ ART ROTTERDAM

Zerp Galerie, Rotterdam

20/06/2021 – 04/07/2021

/ Private Collection Selected By Hans Vandekerckhove

Tatjana Pieters Nieuwevaart 124, 9000 Gent

19/06/21 – 28/08/21

/ PAN Amsterdam

12/12/2020

/ Art Rotterdam

Zerp Galerie, Rotterdam

01/07/2020 – 04/07/2020

/ KIP, Art In Puurs

Village centre Puurs

18/12/2019 – februari 2020

/ PAN Amsterdam

24/11/2019 – 01/12/2019

/ The Glass house on the quai of Puurs-Sint-Amands

13/10/2019 – 15/01/2020

/ Bouwen voor de eeuwigheid (building for ethernity)

Abdijmuseum Ten Duinen Koksijde

22/06/2019 – 05/01/2020

/ Art Rotterdam

Zerp Galerie, Rotterdam

07/02/2019 – 10/02/2019

/ No Man’s Land, Commemorative (WW1) land art sculpture

Pondfarm Langemark-Poelkapelle

03/11/2018

/ Temporary Commemorative (WW1) land art sculpture for the battle of Neeravert

Neeravert Londerzeel

29/09/2018

/ Don’t mention the war

Kunstenhuis Harelbeke

07/09/2018

/ Playing fields

ZERP Galerie, Rotterdam

15/07/2018 – 12/08/2018

/ RAW Contemporary art platform

Boortmeerbeek

08/07/2018 – 26/08/2018

/ SECONDroom Ghent

Ghentbrugge

10/03/18

/ Prize of Buggenhout – Liberal arts prize Pieter Vanneste

Buggenhout

7/10/17 – 29/10/17

/ ‘No man’s land’ mud sculpture in Flanders fields / Expo prize of liberal arts in the city of Harelbeke

Kunstenhuis Harelbeke

11/3/17 – 26/3/17

/ Expo Piet Stoutprize

Beveren-Waas

18/10/2015 – 09/10-2016

/ Birth of a giant

Arts Monopole Sint Amands

18/6 – 19/6

/ Theaterwalk

29/6/2016

/ Introduction to the literary giant

29/5/2016

/ Verhaeren on Tour / Construction of a parade giant

Sint Amands

/ KVDM Artist of the month / Retrospective exhibition

Gent

12/3/16 – 17/4/16

/ Cultuurloft Gent

Gent

20/03/2015 – 29/03/2015

/ Light Cube Art Gallery / solo show

Ronse

01/02/2015 – 08/03/2015

/ Galerie Intuiti Bruxelles

Rivoli Building, Bruxelles

14/01/2015 – 28/02/2015

/ To light up the dark / C&H art space

Amsterdam

18/10/14 – 22/11/14

/ C&H art space and Rob Buelens participated in ‘The Solo Project’ Contemporary Art Fair 2014

Basel Switserland

18/06/2014 – 22/06/2014

/ Hotel Bloom Brussels

Brussel, Sint-Joost-ten-Node

24/04/2014

/ Easter show Rob Buelens sculpture

Townhall Sint Amands

19/04/14 – 21/04/14

/ C&H Art space Amsterdam

Amsterdam

01/10/2013

/ Zwerm

Antwerp, IJzerlaan 30

22/06/13 – 23/06/13

/ Project orgiesculptuur + boekbeelden

Gent

14/06/13 – 22/06/13

/ Sousvoir

kunstroute Hoegaarden

04/05/13 – 05/05/13 & 11,12,18 & 19/05

/ Natuurtalent

Londerzeel

27/04/13

/ Artist of the month Zebrastreet

Gent

01/04/13 – 28/04/13

/ Fly me to the Moon

Dendermonde

29/09/12 – 26/10/12

/ Hard work like building sandcastles

Dendermonde

27/08/12 – Jan 2013

/ Set-Off, Mills of Orshoven, (brewery of Stella)

Leuven

08/0912 – 16/09/12

/ ‘Museumnacht’

Rubenshuis, Antwerpen

04/08/12 – 12/08/12

/’The Circle Game’

Brussel

29/06/12 – 01/07/12

/ ‘Verstilde Beelden’

De Notelaer in Hingene, (neoclassical hunter’s pavillion)

28/04/12 – 01/10/12

/ De Invasie

Ghent

31/03/2012 – 01/04/2012

/ Culture festival, Het Onverdraaglijke

Museum M Leuven

19/10/2011 – 22/100/2011

/ “Artknights”

Zwijvekemuseum door Amuseevous, Dendermonde

07/10/2011 – 27/10/2011

/ Art (silence)

Bibliotheek Kunstwetenschappen Universiteit Gent

5 september 2011

/ ‘Damo arte exterior’

Destelbergen

21/08/2011

/ ‘Bar Jeudi’ Urban Crafts

Café ‘De Storm’ in the MAS museum – Antwerp

28/07/2011

/ ‘Open M’ ‘Staying long enough-leaving on time’

Museum M, Leuven

09/07/2011 – 21/08/2011

/ ‘Beelden in het middelpunt’

Opdorp, Dries

19/03/2011 – 17/04/2011

/ ‘Mise-en-Place/Mise-en-Scène’

Library of Arts sciences of the university of Ghent, curator Dany Deprez

07/02/2011 – 18/03/2011

/ ”Wildvlees solo expo”

Antwerpen, Berchem

02/04/2010 – 03/04/2010

/ ‘De Passionele Moord, interpretaties van de passie van de meester’

Cultural center Doornik

20/11/2009 – 23/12/2009

/ Amuseevous presents: ‘De passionele moord’, ‘Interpretaties van de passie van de meester’

City hall, Leuven

15/09/2009 – 31/10/2009

/ Sculpture exposition ‘Middelpunt van Vlaanderen’

Opdorp, Dries

April 2007

/ Open Monuments day: ‘Wat een Hammekesnest’

Londerzeel Sint Jozef, in the pastor’s garden

09/09/2007

/ group show ‘VANTOT’

Sint Amands

15/04/2006 -16/04/2006

/ School expositions

Sint Lukas Brussels, Sint Lucas Antwerp & Sint Lucas Ghent from 2001 until 2011 (part of the courses)

An ode to cooperation

Text by Filip Luyckx

The typical image of the visual artist is of one who retreats to their studio to work in isolation. At first glance, that might seem solipsistic, but what else can the artist do when the outside world has, to a large extent, lost its sense of community and begun exhibiting increasingly narcissistic traits? This is especially the case if we extend the comparison to past centuries and other cultures. As barometer of their times, the artist is caught between the enduring remnants of timeless logic and self-empathy, and the ephemeral illusions of narcissists lost in their own spectacle. Still, the artist in question does not retreat into satire, instead opting to strike a more positive chord with an ode to the cooperation found within close-knit communities.

From a distance, Rob Buelens’ models intrigue us, but we only gain true insight into the scenes by walking around them and analysing the details from different points of view. Each construction encompasses a great density of activity, teeming with anonymous little figures and layer upon layer of materials. It is comical to observe the masses of Lilliputians joining forces to realise their monumental project, a project far bigger than themselves. There is little doubt as to whether they will succeed, given the ingenuity of their tools and their excellent self-organisation as a labour force. Seen as a collective, it is impossible to single out individuals of greater or lesser talents, but we know that their crew must be some combination of engineers and diligent labourers. Everyone has some skill or other to contribute.

At a scale where infighting is invisible, what emerges before the viewer is a geometric order, a foundational structure that keeps everything on track. Usually this form can be read in the building frame that is under construction, and in the necessary scaffolding and equipment. The composition’s geometry is completed by long strings of people seen mid-movement, pulling and loading. The swarming intermediate stage of the construction constitutes an architecture all of its own. If these works were to grind to a halt, the remnants would resemble those of destroyed or unfinished monuments. It is truly fascinating to observe the actions on the site and to guess at the how and why of it all.

Technical necessity is the hand that spreads out the pieces, like pawns on a chessboard or props on a stage. There are no star actors on this stage, however; here the game is crowd directing, with every figure playing their own modest but indispensable role. This unintended spectacle is not the project of any ruler or architect. All the components of the scene suggest that the participants are conducting their duty in full awareness of its meaningfulness. There is no one in particular seeking to claim the glory. Yet each individual feels valued, and there is no need for group coercion. The tone is much more fantastical and humorous, even bordering on childish. This miniature world will always retain the sense of a relativist utopia in our eyes.

This utopia, the actual objective, is not explicitly visible. The completed form cannot be inferred from the models. The viewer is limited to a point when the works are in full swing.

Which historical era have we found ourselves in? The absence of contemporary technology makes one inclined to situate these scenes in the past. On the other hand, we can observe tools that appear relatively advanced, as well as a sophisticated division of labour and monumental ambitions. So we’re more inclined to see it as a highly developed civilisation – just not our present one. Pyramids, cathedrals and capital city monuments come to mind. The occasional presence of a pulley or crane may provide further hints. The power of the former tool was demonstrated by Archimedes to the King of Syracuse, and the origin of cranes can likewise be traced back to the Greek city-states.

But perhaps the assumption that we are looking at a construction site of a non-specified monument is misleading. Why are we so quick to give our imagination a free pass to exceed sober perception? The model might just as well depict a rehearsal for a theatre production or a design for a film set. In which case, we are witnessing a rehearsal on a stage full of props and extras. Why not? We are ultimately looking at a scene that originates in the imagination. The work does not tout any particular mission or functionality, nor is it a topographic reconstruction of an existing site. In art and architecture, imagination is its own justification. An imagined scenario opens up parallel worlds alongside our own temporal context. An escape to nowhere and everywhere, a source of inspiration that can shape our reality. Even without having a direct influence on architecture, the effects of the imagination affect social life, as well as both individual and collective psychology. There is something that we find endlessly fascinating about the sort of architecture we deem desirable, undesirable or impossible. Our thinking can be influenced by utopian projects, even those that are not even implemented.

A recurring element in the models is that of towers under construction. These vertical towers are often neutralised in the scene by a horizontal construction zone. The tendency towards height in conjunction with large crowds of people harks back to the mythical Tower of Babel, a beloved subject of Pieter Bruegel and his followers. In the Vienna version of his painting, we look out over a vast landscape with a cosmic dimension: the many-sectioned tower reaches into the clouds, while the vast landscape behind it reaches to infinity, and a constant stream of ships can be seen delivering materials. At the same time, the powerful King Nimrod inspects the construction site. Here the community is clearly following top-down instruction, but the tower transcends both the king and the crowd, threatening to overwhelm the sky, the sea and the landscape. We know that the project will fail in the end. For Bruegel, as a Renaissance artist, this subject was an excellent opportunity to depict the Colosseum, drawing on his technical knowledge in the fields of navigation and architecture, and his mastery of the landscape. Bruegel shimmers through in Buelens’ work, though the painter is far from his only source of inspiration. And while he has Bruegelian leanings, his aims do not align with Babel’s, a project as conceited as it is collectivistic. Indeed, it is immensely naive to assume that one could win total control through such a megalomaniacal obsession. The tower is set against an immense landscape and an abundance of details that we can observe if we ourselves manage to keep both feet on the ground. There lies a certain humility in the detail and the cosmic component. Bruegel’s’ Fall of Icarus contains a comparable underlying message. In Buelens’ models, work ethic, humour and solidarity win out over megalomaniacal excesses. Their microcosmic scenes encourage us to rediscover our modest position in the immensity of the wider cosmos.

The biblical allegory of Jacob’s Ladder is often invoked in response to hubristic attempts to scale the highest peaks. While Jacob is dreaming, a ladder is created that serves as a link between heaven and his mind, with angels moving back and forth across it. This story of the spontaneous fulfilment of a promise is a well to which artists have been returning for centuries. Despite the fact that Jacob’s dream takes place in a different dimension than the Tower of Babel, the two are often linked. Buelens’ depictions can be read in many directions. Ultimately, however, the models remain unshakable in their status as artworks. And visionary designs can often prove more influential than well-built architecture.

The Baroque and Neoclassical periods were the heyday of the capriccio in painting and architectural design. The genre evolved from depicting realistic, topographical imagery to increasingly imaginative designs with scarcely any chance of being realised. The resulting concepts had a greater affinity with literature, scenography and printmaking. Nevertheless, some brilliant Baroque architects managed to translate some of their visions into actual structures. Figures like Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, Filippo Juvarra and Luigi Vanvitelli come to mind. Their designs evoke sprawling interior views, with spaces beyond that are sideways or at a higher elevation, all sliding into each other, as it were. Neoclassicism picks up on those concepts, albeit via other stylistic affinities.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi takes that idea to the extreme, making a beeline for utopian territory – entirely impracticable but visionary in terms of influence. It is back to this source that we can trace Etienne-Louis Boullée and the ‘revolutionary’ architects.

What is striking is the gaping disparity between the imagined vision and the practical reality. Visionary examples awaken archetypes in our collective subconscious. They influence us without us knowing; our sensibility evolves in a certain direction without the archetypes becoming real in a literal sense. They already belong too much to the collective symbolic domain for that to happen. The above designers are not simply wayward eccentrics, it turns out. Their proposals are rooted in a deep knowledge of architecture and drawing. They manage to interpret the imminent zeitgeist with great precision. Furthermore, they are able to tap into the archetypes already present in our minds, in such a way that we cannot help but respond, whether through performed aloofness or involvement, blatant rejection or embrace.

Buelens’ models connect with the utopian architects and painters of the capriccio. They manifest like an artistic game, a commentary on society, an archaeological find imbued with a tragicomic undertone that cannot leave us indifferent. They are works that inevitably nestle in our minds, where memory is readily accessible. He directs his models in such a way that they speak to us directly as individuals, not so much as discrete personalities but as members of a community. This is a tendency that is relegated to the background of post-modern cultures in favour of isolated narcissism. Buelens’ depictions thaw within us ancestral memories of times and places where community was still tightly knit and could be mobilised for communal projects. When a community’s greatest achievement was not necessarily in dazzling results but in their potent alliance. The evocation of this in the models possesses a deep symbolic charge that not only stretches back in time but into the mythological structures that we have woven around these time periods. Myths, facts and symbols can hardly be separated here; they form an unbreakable whole.

These processes of influence take place in real time, as well as on mythical and symbolic timelines. What we imagined and how we experienced it is of equal weight to the actual facts. The image of the tight-knit community that we could be part of – today we might even describe it as a utopian community – appeals strongly to our inherent love of cooperation. The constructions are integrated in the borderlands between the imaginary and the real world. They could have once been there, and perhaps they never existed in this way, but they are a real part of our symbolic sense of time.

Each model contains a world so rich in and of itself that we might almost forget that visual communication is possible with other models and with the surrounding environment as a whole. When exhibited together, the visual presence of the artworks expands. The more miniature worlds are locked together, the greater the interplay of scenes and the broader the scope of their meaning. That dialogue also plays out between the models and the artefacts – artistic, archaeological, or otherwise – that are present in the museum where they are exhibited. Due to their accessible and small-scale nature, Buelens’ scenes integrate wonderfully with the other elements in the museum. Their presence is neither ostentatious nor disruptive. Inevitably, however, their presence does influence how we view the stories of the other museum objects. With their relativistic humour, they have the ability to keep us humble. They also serve to illustrate the fact that there is so much intelligent and emotional life beyond what we can see – just over the horizon, in other times and cultures, and spanning innumerable subjects. Above all, we learn that human endeavour stands or falls on our capacity for cooperation. Food for thought in a culture of narcissism.

Een hommage aan de samenwerking

Tekst door Filip Luyckx

Vaak stellen we een beeldende kunstenaar voor als iemand die teruggetrokken in zijn atelier eigenzinnig zijn ding doet. Op het eerste gezicht zou dat solipsistisch kunnen lijken, maar wat rest de kunstenaar te doen wanneer de wereld daarbuiten voor een goed deel haar gemeenschapszin is kwijtgespeeld en alsmaar meer narcistische trekken vertoont. Dat gaat zeker op als we de vergelijking doortrekken met vorige eeuwen en andere culturen. Als graadmeter van zijn tijd wordt de kunstenaar dan heen en weer geslingerd tussen de overblijfselen van tijdeloze logica en empathie in hemzelf en de efemere illusies van narcisten die zich onderdompelen in hun eigen spektakel. Nochtans neemt de kunstenaar niet zijn toevlucht tot de satire maar bespeelt hij juist de positieve noot bij middel van een hommage aan de samenwerking binnen hechte gemeenschappen.

De maquettes van Rob Buelens intrigeren ons van op afstand, maar we krijgen pas inzicht in de taferelen door er rondom te lopen en de details te analyseren vanuit verschillende gezichtspunten. Elke constructie ontvouwt een drukte van jewelste, het wemelt er van anonieme figuurtjes en opgestapelde materialen. Het lijkt komisch omdat een massa lilliputters zich met vereende krachten uitslooft voor een monumentaal project dat boven hun petje reikt. Hoewel er weinig twijfel over bestaat dat ze hun einddoel zullen bereiken, gezien de vindingrijkheid van hun werktuigen en arbeidsorganisatie. Onder de menigte vallen er geen grotere of mindere talenten te onderscheiden, maar we weten dat de ingenieurs en de noeste arbeiders er allemaal ergens tussen zitten. Iedereen draagt naar eigen kunde zijn steentje bij en er wordt verder niet over gezeurd, want de voltooiing zal voor iedereen een wereld van verschil uitmaken.

Voorbij het oppervlakkige geharrewar valt er een geometrische ordening te bespeuren, een basisstructuur die alles in goede banen leidt. Meestal valt die vorm af te lezen uit het huidige bouwskelet, aangevuld met de onvermijdelijke steigers en apparaten. Slierten mensen in samenhang met de trek- en laadbewegingen van de primitieve machines vervolledigen de geometrie van de compositie. Die wervelende tussenfase van de opbouw vormt een architectuur op zich. Zou het werk hier stil vallen, dan zou het relict kunnen wedijveren met de restanten van vernielde of onvoltooide monumenten. Hoe fascinerend is het niet om bouwactiviteiten gade te slaan en te gissen naar het hoe en waarom van de handelingen. De technische noodwendigheid zet de stenen en de pionnen uit over het terrein, zoals een enscenering op een podium. Steractoren ontbreken evenwel, beter spreken we van een massaregie waarin elke schakel zijn bescheiden maar onmisbare rol vervult. Dat ongewild spektakel wordt niet gestuwd door de onzichtbare hand van een vorst, een mecenas of een toparchitect. Alle ingrediënten van de scène suggereren dat de deelnemers elkaar motiveren, ze voeren zonder veel omhaal gewoon hun taak uit, in het volle besef van de zinvolheid ervan. Niemand in het bijzonder wil alle eer opstrijken. Nochtans voelt elk individu zich gewaardeerd, er is geen sprake van collectieve dwang. Daarvoor lijkt alles te fantasievol, vol humor, zelfs een tikkeltje kinderlijk. Tenslotte zal deze miniatuurwereld in onze ogen altijd het gehalte behouden van een relativerende utopie.

Helemaal buiten beeld blijft die utopie – de eigenlijke doelstelling. Uit de maquettes valt geen voltooide vorm af te leiden, noch een functie of betekenis. We weten evenmin iets over de tijdsduur van het bouwproject. Ooit was er een voor en ooit zal er een na zijn, maar dat lijkt nu helemaal niet aan de orde. Als toeschouwer verschijnen we te midden van de volle werkzaamheden. Er is al aardig wat werk verzet en er ligt er nog meer voor de boeg. Wie intens in zijn bezigheid opgaat houdt er een andere tijdsbeleving op na dan de buitenstaander. Voor de geëngageerde deelnemers verloopt de werkdag sneller dan de klok, maar de voltooiing ligt in hun ogen dan weer onmetelijk ver af – wellicht een eeuwigheid. Toch zal de geschiedenis dat ooit maar een beperkte periode vinden binnen een oneindig geheel. Alle deelnemers zijn het er wel over eens dat hun werk nuttig en zinvol is voor henzelf en de volgende generaties. De voltoiing zal een substantieel verschil uitmaken ten opzichte van de aanvankelijke afwezigheid van het project, al hebben sommige arbeiders die situatie nooit gekend en zullen andere collega’s het eindpunt nooit beleven. Iedereen voelt zich gemotiveerd vanuit het huidige bouwschema. Ondanks alle motivatie en technisch vernuft hangt er een onuitgesproken onzekerheid over het project. Tal van hindernissen kunnen onderweg opduiken, maar evenzeer kunnen de bouwers van idee verzinnen en hun project bijsturen. Het blijft spannend zolang de trofee niet is binnengehaald. Juist dit feit houdt het vuur van de motivatie brandend. Als het bepalen van de projectduur al een dubbeltje op zijn kant is, is het nog meer gissen naar de chonologie van de taferelen. In welke historische periode bevinden we ons hier? Door de afwezigheid van state-of-the-art technologie hebben we de neiging om de scènes in het verleden te projecteren. Anderzijds merken we voor hun tijd geavanceerde werktuigen op, alssok een volleerde taakverdeling en monumentale ambities. Dus opteren we voor een hoogontwikkelde beschaving maar niet de huidige. In gedachten komen piramiden, kathedralen, hoofdstedelijke monumenten. De sporadische aanwezigheid van een katrol of een hijskraan verschaft mogelijk een lichte aanwijzing. Het eerstgenoemde werktuig werd door Archimedes voorgesteld aan de koning van Syracuse, terwijl de oorsprong van hijskranen eveneens zou terugreiken tot de Griekse stadstaten.

Misschien zet de aanname dat we naar een bouwplaats kijken van een niet nader geïdentificeerd monument ons op het verkeerde been. Waarom geven we onze verbeelding meteen een vrijgeleide om voorbij de nuchtere waarneming te hollen? Een maquette zou ook een generale repetitie van een theatervoorstelling kunnen zijn, of een ontwerp voor een filmset. In dat geval kijken we naar een podium vol rekwisieten en figuranten. Waarom niet? Uiteindelijk komt het tafereel voort uit de verbeelding. Er is geen opdracht of functionaliteit mee gemoeid, noch een topgrafische reconstructie van een bestaande site. De verbeelding bezit het volle bestaansrecht in de kunsten en de architectuur. Een fantasievoorstelling opent parallelle trajecten naast ons tijdskader. Een ontsnapping naar nergens en overal, een inspiratiebron die vorm kan geven aan onze werkelijkheid. Zelfs zonder directe invloed op de architectuur reiken de effecten van de verbeelding tot in het sociale leven, alsook in de individuele en collectieve psychologie. De architectuur die we wensen of vrezen en vaak voor onmogelijk houden fascineert ons onophoudelijk. Alle onverwezenlijkte, zelfs utopische projecten beïnvloeden onze gedachtengang. Doorheen de maquettes duiken in aanbouw zijnde torens op die binnen het tafereel vaak worden geneutraliseerd door een horizontaal constructieterrein. Die combinatie van hoogtedrang en mensenmassa reikt terug tot de mythische Toren van Babel, een geliefd onderwerp bij Pieter Breugel en zijn navolgers. In de Weense versie van het schilderij turen we over een weids landschap met een kosmische dimensie: de meerdelige toren reikt tot in de wolken, het landschap erachter staat op oneindig, op zee voeren schepen constant materialen aan. Intussen inspecteert de machtige koning Nimrod de bouwwerf.

De gemeenschap volgt hier duidelijk een dictaat van bovenaf, maar de toren overstijgt zowel de koning als de menigte en dreigt de hemel, de zee en het landschap te overweldigen. We weten dat het project uiteindelijk faalt. Voor Breugel was dit onderwerp een uitstekende gelegenheid om als renaissancekunstenaar het Colosseum uit te beelden, samen met zijn technische kennis van van de scheepvaart, de bouwbedrijvigheid en de regie van het landschap. Bij Buelens zindert Breugel nog ergens na, maar dat is zeker niet zijn enige inspiratiebron. Tevens leunt hij meer aan bij Breugel dan bij het streefdoel van Babel, dat verwaand en collectivistisch overkomt en ook immens naïef is om te veronderstellen dat een megalomane obsessie de totale controle zou opleveren. De toren positioneert zich immers tegenover een onmetelijk landschap en een overvloed aan details die we opmerken als we met beide voeten op de grond blijven staan. De nederigheid schuilt zowel in het detail als in de kosmische component. Breugels “Val van Icarus” bevat een vergelijkbare onderliggende boodschap. In de maquettes van Buelens halen de arbeidsvlijt, de humor en de samenhorigheid het op megalomane uitwassen. De miniatuurscènes zetten ons aan tot het herontdekken van onze bescheiden positie in immense gehelen.

Tegenover de verkrampte pogingen om de hoogste toppen te scheren wordt vaak de bijbelse allegorie van de Jakobsladder aangehaald. Tijdens een droom verschijnt er vanzelf vanuit de hemel een ladder met heen en weer lopende engelen tot binnenin Jakob’s geest. Dit dankbare thema van een spontane vervulling van een belofte maakte eeuwenlang furore onder kunstenaars, die telkens andere varianten bedachten. Een dergelijke mysterieuze tegemoetkoming vinden we terug in de popsong “A Stairway to Heaven” van Led Zeppelin. Jakobs droom voltrekt zich weliswaar in een andere dimensie dan een Toren van Babel. Vaak worden beide thema’s aan elkaar gelinkt. De voorstellingen van Buelens kunnen in alle richtingen worden geïnterpreteerd. Het bouwproject kan falen maar tegelijk de gemeenschap behoeden voor grotere rampen. Als puntje bij paaltje komt zweren de maquettes bij hun voortbestaan als kunstwerken. Visionaire ontwerpen blijken vaak invloedrijker dan veel uitgevoerde architectuur.

Tijdens barok en neoclassicisme vierde het capriccio in de schilderkunst en het architectuurontwerp hoogtij. Vanuit de topgrafische weergave gleed het snel af tot de meest fantasierijke ontwerpen met nauwelijks vooruitzicht op daadwerkelijke uitvoering. De vrijgegeven concepten vertoonden meer verwantschap met literatuur, scenografie en prentkunst. Niettemin slaagde een aantal geniale barokarchitecten erin een deel van hun visie naar concrete bouwvolumes te vertalen. In gedachten verschijnen figuren als Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, Filippo Juvarra en Luigi Vanvitelli. Hun ontwerpen roepen schier uitdeinende binnenaanzichten op, er liggen ruimtes verderop, zijwaarts of hoger en ze schuiven als het ware in elkaar. Het neoclassicisme pikt in op die concepten maar vanuit andere stijlaffiniteiten. Giovanni Battista Piranesi drijft dat idee ten spits en begeeft zich voluit op een utopisch terrein, dus onuitvoerbaar maar visionair wat invloed betreft. Vanuit die bron ontspruiten Etienne-Louis Boullée en de ‘revolutionaire’ architecten. In het oog springt het hemelsbreed verschil tussen ingebeelde visie en praktische werkelijkheid. Visionaire voorbeelden wekken archetypen op in ons collectief onderbewuste. Ongewild ondergaan we hun invloed en evolueert onze sensibiliteit in een bepaalde richting, zonder dat de archetypen op een letterlijke manier werkelijk worden. Daarvoor behoren ze al te zeer tot het collectieve symbolische domein. Bovengenoemde ontwerpers blijken niet zomaar wispelturige zonderlingen te zijn. Hun voorstellen ontspruiten aan een diepgaande kennis van architectuur en tekenkunst. Ze vertolken precies de aankomende tijdgeest. Tevens tappen ze uit aanwezige archetypen in onze geest, waardoor we niet anders kunnen dan erop te reageren, of dat nu gepeelde afstandelijkheid of betrokkenheid is, felle afwijzing of aantrekking.

De maquettes van Buelens vinden aansluiting bij de utopische architecten en schilders van het capriccio. Ze manifesteren zich als een artistiek spel, een maatschappelijke commentaar, een vondst met tragikomische ondertoon die ons niet onverschillig laat. Ze nestelen zich onvermijdelijk in ons geheugen van waaruit de herinnering beschikbaar is wanneer er aanleiding toe is. Buelens’ geregisseerde modellen spreken ons onmiddellijk aan als individu, niet zozeer in onze persoonlijkheid maar wel in ons handelen als leden van een gemeenschap. Dat is het terrein bij uitstek dat in westerse postmoderne culturen werd achteruitgeschoven ten voordele van een geïsoleerd narcisme. Buelens’ voorstellingen weken in ons ancestrale herinneringen los aan tijden en plaatsen waar de gemeenschap wel nog hecht in elkaar stak en zich mobiliseerde voor gemeenschappelijke projecten die veel weg hebben van utopische monumenten. Hun grootste verwezenlijking schitterde niet noodzakelijk in het eindresultaat maar in het functionerende samenwerkingsverband. De evocatie daarvan in de maquettes bezit een diepe symbolische geladenheid die niet alleen ver terugreikt in de tijd maar ook in de mythische structuren die we rond de tijdsperiodes hebben geweven. Mythen, feiten en symbolen kunnen hier moeilijk uit elkaar worden gehaald, ze vormen immers een onverbrekelijk geheel. De beïnvloedingsprocessen spelen zich zowel af in de reële tijd als in mythische en symbolische tijdlijnen. Wat we ons voorstelden en hoe we dat ervoeren legt minstens evenveel gewicht in de schaal dan de feitelijkheden. Het beeld van de hechte gemeenschap – we zouden tegenwoordig durven spreken van een utopische gemeenschap – waar we deel van zouden kunnen uitmaken, appelleert sterk aan ons onbehagen over het ontbreken van een dergelijke gemeenschap. Het realiteitsgehalte van de constructies doet er niet toe, ze integreren zich in het grensgebied tussen de imaginaire en de reële wereld. Ze hadden er ooit kunnen zijn en wellicht hebben ze op die manier nooit bestaan, maar ze maken wel deel uit van ons symbolisch tijdsbesef.

Elke afzonderlijke maquette ontvouwt een wereld op zich, waardoor we haast zouden vergeten dat de transparante glasplaten visuele communicatie toelaten met zowel andere maquettes als met de volledige omgeving. Vanuit hun nabuurschap breidt de visuele verschijning van de kunstwerken zich uit. Het samenspel van meerdere taferelen verbreedt de betekenisgeving, doordat nog meer miniwerelden in elkaar schuiven. Die dialoog speelt zich eveneens af tussen de maquettes en de aanwezige artefacten in het museum – artistiek, archeologisch, om het even wat. De modellen gedragen zich niet ostentatief en treden evenmin op als stoorzenders. Wel beïnvloedt hun aanwezigheid onvermijdelijk onze blik op het verhaal van de andere museumobjecten. Met hun relativerende humor plaatsen ze iedereen terug met beide voeten op de grond. Ze illustreren ook dat zoveel intelligent en emotioneel leven zich afspeelt buiten onze gezichtseinder onder andere horizonten, in andere tijden en culturen, doorheen ontelbare onderwerpen. Vooral leren we dat menselijke ondernemingen steunen of vallen bij monde van een schare medewerkers. Een doordenkertje in de cultuur van het narcisme.